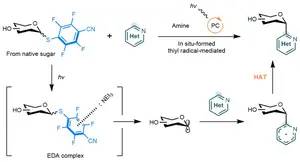

There are three main kinds of sugars: fructose, glucose, and sucrose. Sucrose is more complex and is often what you find in refined sugars, which is what you then find in the likes of cookies, cakes, and candies. On the other hand, fruit generally contains fructose and glucose separately — independent of each other and doing their own metabolic things.

This divergent digestion process, combined with the fiber in any given fruit, allows the sugars to be absorbed into our bodies in a more balanced way. This dynamic is reflected in the glycemic index (GI). The greater a fruit’s GI score, the quicker it tends to spike blood sugar levels. A GI of 55 and below is considered low, while 56 to 69 is medium, and 70 or above is high. That means even fruits with deceptively low sugar content can have an impact on our blood sugar.

For this ranking, however, we focused on the amount of sugar per 100 grams of fruit. While we took glycemic index and glycemic load into account, we’ve ranked 13 popular fruits in order from lowest to highest sugar content. Learn more about our methodology at the end.

Read more: 13 Meats That Are Now Illegal In The US

Watermelon

A whole watermelon next to watermelon slices – Photoongraphy/Shutterstock

The watermelon not only has a notable, complex, and even important place in the cultural history of the United States, but it also offers more versatility than you may think. You can freshen up a salad with it, grill the red-and-green delight into a charred, barbecue favorite, or even turn it into a summer-friendly watermelon soup. No wonder it’s as popular as any other fruit out there. The U.S. produces almost 4 billion pounds of watermelon a year – third after apples and bananas in availability – with Florida handling about a quarter of that load.

Yes, watermelon in a nutritional sense is a great source of hydration, potassium, vitamins A and B6, and lycopene. It typically contains 17 grams of sugar per wedge, which equals approximately 6.2 grams per 100 grams of fruit.

Despite this low number, it’s worth noting that watermelon has one of, if not the, highest GI scores of any popular fruit: between 72 and 76. This is due to the melon’s extremely low fiber count for the sweetness it brings. Next time you’re biting into a drippy slice of watermelon and thinking that at least it’s better than a candy bar, remember this: a Snickers bar has a GI over 20 points lower.

Cantaloupe

Hands holding a cantaloupe from a freshly picked bunch – Petesphotography/Getty Images

Cantaloupe not only offers benefits in terms of eye health, immunity, and digestion, but it also offers a relatively modest amount of sugar per 100 grams. To be specific, it contains roughly 7.9 grams of sugar per 100 grams, with the rest of the fruit being mostly water.

The fruit is a staple of fruit salads, beach hangs, and continental breakfast buffets. However, some fans may want to take note of its glycemic index. Cantaloupe can have a medium GI score of around 65. For that reason, those with diabetes are often advised to consume melon in moderation.

Beyond its sugar content, cantaloupe has quite the nomadic backstory. Nobody’s sure exactly where the cantaloupe originated, but legend has it that it made its way into the grateful mouth of a 15th-century pontiff in Italy – Pope Paul II – where he enjoyed the exotic melon on his country estate. The fruit was named after that estate town on the outskirts of Rome: Cantalupo, where wolves gathered to sing.

Kiwi

A whole kiwi alongside cut kiwis on a white background – Oleh V/Shutterstock

Kiwi is a fruit that often gets overlooked, judging by the fact that it placed 19th on a YouGov fruit popularity poll behind the likes of Granny Smith apples, blackberries, and clementines. That is, until someone decides to cut one open, maybe do the pain-in-the-butt peeling for you (although you can just eat the skin). Then, all of a sudden, people nearby are clamoring for a slice. There’s a reason it’s half of what’s considered the GOAT Snapple flavor.

The kiwi originally comes from China, where roughly two-thirds of the world’s kiwis are still produced. This fuzzy fruit (which is actually a type of berry) is great for gut health, vitamin C, vitamin E, antioxidants, and other nutritional benefits. It’s also relatively moderate in terms of sugar, with 9 grams per 100-gram serving.

However, the sugar content of kiwi (which is moderate to begin with) spikes as it ripens. If you’re trying to keep an eye on blood sugar, you may want to consume kiwi in moderation. The GI score can reach as high as the 50s, though it usually measures at around 47 or so.

Orange

Cut orange on a white background – T_kimura/Getty Images

We all love an orange. We love the juicy, semi-tart sweetness. We love the drop-kick of vitamin C it brings. We love its flavoring for takeout chicken. We love when someone puts an entire slice in their mouth and smiles. For all these reasons and more, the brightly colored sphere has long been among the most consumed produce in the U.S. About 4 million tons are grown each year, averaging about 15 pounds consumed per person.

In general, 100 grams of your average orange rocks about 9.4 grams of overall sugar. However, a large orange might contain as much as 17 grams. The good thing is that the fiber in an orange can slow down absorption and regulate its assimilation, accounting for the fruit’s GI score sitting at around 45.

The not-so-good thing? That fiber is gone once the orange is turned into juice. With the sugar getting concentrated in this process, enjoying a glass of OJ, no matter the brand, can be no different than having a soda. That’s never a good sign for anybody’s sugar intake. And a lot of us drink the stuff, to the tune of over 70 pounds annually for your average American.

Pineapple

Whole and sliced pineapple on a cutting board – Ink N Propeller/Shutterstock

Brazilians have a saying used to describe a major problem that has to somehow be solved –”descascar o abacaxi,” or “to peel a pineapple.” Anybody who has ever tried to do just that will happily back up that idiom. But here’s a brain-twister. What if the pineapple is the problem? Is the pineapple then like peeling a pineapple? These questions may be too big for mere mortals to wrestle with. Let’s just focus on something much sweeter: the sugar content of pineapple.

For every 100 grams of pineapple, you’ll consume around 9.9 grams of sugar. Alongside this sugar, you’ll also find a ton of vitamins, minerals, fiber, and nutrients that give it anti-inflammatory properties.

Pineapple, being moderate in fiber and high in sugar, has a GI count higher than many other popular fruits, at around 59. So, even though you’re getting nutritional upside, too much pineapple may raise your blood sugar levels. This is obviously exacerbated when the fruit comes canned and bathed in sugary syrup — or, surprisingly, when a pineapple is turned upside down.

Banana

Whole, peeled, and cut bananas swirling against a white background – Everyday Better To Do Everything You Love/Getty Images

When accounting for sugar intake, the ripeness of a fruit matters. As fruit ripens, its enzymes break down starches into simple sugars. This is why unripe fruit tastes starchy and ripe fruit tastes sweet. That uptick in sugars, however, can bring down a fruit’s nutritional profile. The riper a fruit gets, the higher its sugar content, and the lower the fiber count. Bananas, in particular, contain an advantageous carbohydrate called resistant starch when they are still green. It may not be the best-tasting version of a banana, but that starchy stage is great for your gut, metabolism, and blood sugar.

However, when that bad boy starts to turn yellow, the prebiotics disappear with the starch, and the sugars take over in full force. Yes, that means you can now make some delicious banana bread. But that also means the bananas contain more sugar the more they brown.

The average banana contains 12 grams of sugar. This number can increase, as can its average GI score of 48. Sure, you’re still getting the potassium and vitamin B6 for which the curved comestible is known. And, sure, it can still make for a solid silly-pretend phone. Just keep this rhyme in mind for the banana: yellow-brown brings the nutrition down.

Pomegranate

A bundle of cut-open pomegranates – Denys Popov/Getty Images

The pomegranate, clocking in at 14 grams of sugar per 100 grams, is one of the more sticky-sweet fruit-eating experiences. The relatively high sugar count shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, considering that munching on the seeds is akin to digging into a delicious bowl of candy. The difference being that this is a bowl put out by nature instead of granny.

It’s amazing that while pomegranate is a famously messy fruit, it is also one of the very oldest domesticated fruits in the history of civilization, originating in an area stretching from contemporary Iraq to the Caucasus. It’s also been suggested that the forbidden fruit Adam and Eve naughtily munched on wasn’t meant to be an apple, quince, or fig, but a pomegranate. You have to admit that big, red skin is tempting (with or without a snake making its pitch), and once the pioneering pair discovered what was inside, forget it, paradise was doomed.

Granted, before the trespassing couple got tossed out of Eden, they could’ve made their case to God that the pomegranate’s GI score is only about 35, putting it in the low category. And that they’re also rich in antioxidants, fiber, several vitamins, and other elements great for a healthy heart. Maybe the big guy would have changed his mind.

Mango

A whole mango and a cut mango on a white background – Photoongraphy/Shutterstock

Mangos are difficult to peel but easy to love, thanks to their juicy sweetness. Unsurprisingly, the mango has apparently become the most popular fruit in America. Or at the very least, it’s the most Googled fruit. Certainly, that’s an indicator of popularity. Who searches the internet for things they hate? (You know what, don’t answer that.) What is certain is that mango consumption has doubled in the U.S. since 2005.

The fruit contains roughly 14 grams of sugar per 100 grams, which makes it higher in sugar than many other fruits. Conversely, mangos boast a GI score of around 50. That means mangos sit in the low category of GI scores, despite their renowned sweetness.

Thanks to its tastiness, the fruit was venerated on the Indian subcontinent for thousands of years before the Portuguese brought it over to the Western Hemisphere in the 1500s. To this day, the mango is the national fruit of both India and Pakistan and the national tree of Bangladesh. Not only is it delicious (thanks in no small part to its sugar content), but it has loads of vitamin C and potassium, as well as being anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory.

Lychee

A whole and a peeled lychee on white background – MERCURY studio/Shutterstock

Nutritionally, lychees are potent, teeming with flavonoids and polyphenols, vitamin C, potassium, manganese, and other human-boosting properties. However, they are also quite high in sugar, with around 15 grams per 100-gram serving. The lychee’s GI score is usually around 50.

But when you have ancient Chinese emperors sending underlings on thousand-mile horseback journeys to fetch you, you must be pretty damn good. According to legend, Emperor Xuanzong did just that in order to impress his lover. The lychee is a Southern Chinese original that has gained popularity across the world. And why not? The pink-red-skinned, white-meated fruit is a sign of good fortune, a symbol of love, and contributes to an absolute doll of a martini.

When it’s canned in syrup, however, the real sugar issues can emerge. Lychees swimming in sweet syrup in a tin can contain as much as 22 grams of sugar, with GI scores close to 80. This fact hasn’t slowed consumption of the fruit in this way, as the market for canned, ready-to-eat lychees is very much trending up.

Fig

Figs on a platter – Igorr1/Getty Images

If you thought the mango was an old fruit, meet the fig. Its cultivation stretches back over 10,000 years to the beginnings of civilization in the Middle East. It was possibly the first domesticated fruit in human history. Figs were also some of the very first sweeteners used in food, ever. Eat your heart out, Splenda.

No surprise then that figs — dried figs, at least, which are arguably their most common form — are high in the sweet stuff. For every 100 grams of fresh figs, you’ll consume around 16 grams of sugar. This number soars to a whopping 48 grams of sugar per 100 grams of dried figs, with a high-ish GI score of around 61.

That means those cautious of their blood sugar levels may want to monitor portions of the stuff. But vegans have the all clear to enjoy them, for the most part. You see, despite the fact that many figs need a fig wasp (not as scary as it sounds) to pollinate, the majority of figs we eat are not filled with wasp eggs. Despite the occasional insect symbiosis, figs are foundational fare for our species. They are loaded with goodies like potassium, magnesium, iron, and, yes, even copper if you’re on the lookout.

Raisins

Raisins falling against a white background – Andrey Elkin/Getty Images

It’s remarkable how a particular food can go from one end of the health spectrum to the other, with just a bit of alteration. Let’s take the grape, for example. Fresh grapes — whether red or black — are filled with all kinds of good stuff that offset the sugar count. Plus, you’re getting extra potassium when you dig into this winemaking vine-marble.

The sugar in the grape becomes a problem upon transformation into a raisin. The drying out has negative nutritional effects. When you pick up a raisin, you’re holding something that contains 59 grams of sugar for 100 grams, and over 100 grams for a cup. You’re also looking at an unfavorable GI score for the shriveled snacks, upwards of 64.

Despite becoming a low-key sugar bomb because the water is removed, raisins still offer health pluses. They’re excellent when it comes to antioxidants (so that’s not lost in the de-graping process). The same goes for the potassium. And they’re rich in other beneficial, bioactive compounds. Plus, raisins, like all dried fruit, can keep you regular and save you from constipation. Yay for that.

Dates

Bowl of dates – Nungning20/Getty Images

After being cultivated for more than six millennia, since its agricultural origins in the ancient Middle East, the date has become a symbol of life and fertility across a multitude of ethnicities and faiths. Today, there are over 200 kinds of dates in the world.

One date can contain as much as 16 grams of sugar. For every 100 grams, they can contain 63 grams of the sweet stuff. GI scores for dates usually hover around 42, but some boast scores as high as 75. Being that most of a date’s calories are derived from sugar (it’s 80% of a date’s makeup, after all), and it’s more often than not eaten in its ripened stage, too much of a helping can lead to surprisingly high sugar intake.

The nutritional value of the sweet, leathery fruit — including its sugar content — can range drastically across the many variations. But no matter the type, dates have certain nutritional benefits, especially in the realms of gut, heart, and brain health, as well as energy levels. But it’s also yummy. The Medjool variety is especially delicious, and a popular satiater during Ramadan.

Methodology

Bowl of fruit salad – Fordvika/Getty Images

Every fruit comes in a different portion size. That’s why we decided to standardize the portion for this ranking, with every fruit ordered from the one with the least to the one with the most sugar per 100 grams.

The thing is, pure sugar count is not actually indicative of how that particular fruit’s sugar is going to affect one’s body. That’s why we also delved into metrics like the glycemic index, averaged out between different medical and nutritional sources. These measurements revealed the sweet fruits that could have direct, sugar-based downsides. And thus, this list sprouted from a pit into a flower that you can now eat (with your mind).

For more food and drink goodness, join The Takeout’s newsletter and add us as a preferred search source. Get taste tests, food & drink news, deals from your favorite chains, recipes, cooking tips, and more!

Read the original article on The Takeout.